The Moral Was Completely Different in the Book: Why Stanley in 'It Chapter Two' Chose to End It All

The king of horror would never have written it that way.

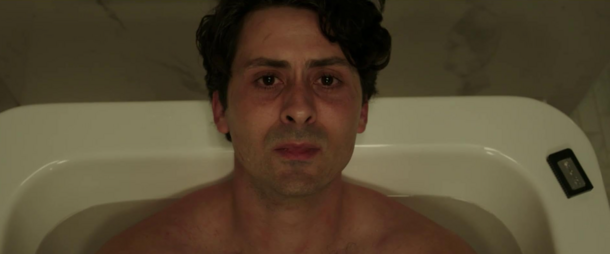

When Stanley Uris dies by suicide in It Chapter Two after Mike's phone call, the scene feels frightening, yet eerily calm. His actions are even given a kind of explanation: he couldn’t be the weak link, so he chose to remove himself so that the others could unite and defeat the evil. Stanley even writes a touching letter, calling his choice "not cowardice, but a necessary decision."

It turns into an act of self-sacrifice — he voluntarily "removes himself from the equation" for the sake of victory over evil.But in Stephen King’s original novel, things are very different. And far more honest.

In the original book, Stanley doesn’t take his life out of some heroic resolve to help his friends — he simply can’t handle it. Unlike the rest of the Losers’ Club, who forget much of what happened during their childhood, Stan remembers every horrifying moment when Pennywise returns to Derry. And that weight is too much for him to carry.

He doesn’t want to go back to Derry. He doesn’t want to face again what nearly killed them all. He doesn’t want to live with that knowledge. He just can’t.

There’s no romanticizing in King’s version. Stan doesn’t leave letters, doesn’t explain or justify himself. He simply goes into the bathroom, does what he does, and writes a single word in blood on the wall — IT. It’s a desperate act, not a calculated one. And that’s the core of King’s writing: he doesn’t romanticize death, especially not this kind. He shows it as what it is — horror, weakness, a tragedy that breaks lives and destroys friendships.

So why did the film change this moment so drastically? Perhaps to justify the screen time devoted to young Stanley in the first part. Perhaps to avoid leaving the audience on such a grim note. Or maybe the filmmakers simply didn’t have the courage to say: "Yes, it was terrifying. Yes, someone didn’t make it."

The movie turned Stan’s suicide into something close to heroism. But therein lies the danger: when death is framed as a noble sacrifice for the greater good, it stops being a personal tragedy. It becomes a tool. And that is a lie.

In King’s story, Stan doesn’t die a hero. He dies a broken man. And maybe, in that, there’s far more truth than in any farewell letter.